Welcome to Fallas

The craziest, fieriest, noisiest week in the Valencian calendar is here - fancy a tour?

It’s always been curious to me how Valencia has managed to stay under the radar as a city. I first came here, twelve years ago in 2011, somewhat by accident, before finally moving here in 2019. Since then I’ve been surprised to see that it’s remained relatively unknown up until the last year or two when, post-pandemic, the horizons of the world’s workers have opened up.

But even as the rental prices skyrocket and the number of shop-workers speaking to you in castellano plummets, the city still feels resolutely Valencian. Many locals comment that Valencia is more like a big town than Spain’s third biggest city, and the connection to the land and sea here is strong. Indeed, opposite the iconic Arts & Sciences building is where the huerta (Valencia’s agricultural fields) starts. You can quite literally look across the dual carriageway from the towering Oceanographic and see a small hut on the edge of a farmed field. The gateway to a different kind of life which, even as recently as the 1960s, crept closer to the old city walls.

Along with the ‘big town’ comment, I’ve also lost track of the number of locals who have told me, unprompted, that Valencians can be ‘very closed’, and especially when compared to big city Madrileños whose ‘openness’ they refer to as contrast, not always entirely complimentarily. Maybe it’s for this reason that Valencia has remained one of Spain’s best-kept secrets. With three hundred days of sun per year, beautiful beaches and stunning mountains, I can see why they’d keep it close to their chests.

What I can’t understand, though, is how they’ve managed to keep one of the biggest, noisiest, and maddest of all Spanish fiestas under their hats: Falles (or Fallas, in castellano).

Falles has never made it into the rest of the world’s cultural map of Spain, in the same way, say, that the San Fermin fiesta in Pamplona (the famous bull run), or La Tomatina (also in the wider Valencia community, in Buñol) both have. And I have no idea why, because it’s a month-long, noisy as hell (seriously, think endless explosions, day and night), really fun, and unlike anything else I’ve experienced anywhere else.

Falles runs every year from 15 - 19 March (though starts from the end of February) and encompasses many different traditions and activities. At its most full-on, it’s not for the faint-hearted. Think all-night parties for days on-end, small children throwing firecrackers at you and substantial ear damage; it divides Valencianos, many of whom leave town. On the tamer side, it’s an ushering in of Spring, a chance to walk the streets taking in the art work on show, watch some firework displays, and spot the shimmering silk dresses of the falleras and falleros making their way to offer flowers to the Virgin Mary.

I’ve celebrated Falles about three times and this year was hoping to do so again, documenting parts of it here. Sadly, in the end I’ve come down with a nasty virus that’s had me off-kilter for over a week (and barely able to speak, the horror). So much of this tour will use photos from previous years, though I hope to make it out for a short walk today to see my only mascletá of this season and a few of the monumentos. No idea what I’m talking about? No worries, just walk this way!

Also, before we begin, a couple of disclaimers:

Most of my knowledge here is what I’ve gleaned from Valencian / friends based here and my years living here. There are also many legends about Falles that mean no one is entirely sure of origins of certain traditions. If there’s anything I’ve missed out or am incorrect on, please do drop me a comment. I am still learning myself and offer this as an insight into Valencian life, not a certification.

Falles is a proudly Valencian festival but unfortunately I don’t speak Valenciano, so I’ll use the word Fallas and mostly use Castilian Spanish phrases.

I am by no means a gifted photographer, as you’ll see from these photos. They are (unless otherwise stated) all mine though, so think of this as a tour from a friend, not a professional guide!

What is Fallas?

Explaining Fallas to the uninitiated is like the first time I explained the concept of Christmas Pudding to a non-Brit (seriously, try it and realise just how insane that medieval recipe sounds). Both also end in flames.

That’s all to say: please bear with me.

Every year between 15 and 19 March, Valencia’s Fallas festival takes over the streets of Valencia to mark the Spring Equinox. On the face of it it seems like one big street party: roads are closed, huts are opened selling churros, pumpkin buñuelos and, very popular, beer and mojitos. Marquees are erected on every street (called Verbenas) and DJs set up their booths to pump out music. Fireworks and firecrackers are allowed to be sold, and children as young as eighteen months roam the streets gleefully throwing them at one another.

But this is not just a party. Alongside each marquee, on what feels like every other road, is a towering structure, made out of wood, papier mache and, often nowadays, polysterene. These are the Fallas from which the festival takes its name, and are often created to show fantastical characters and scenes. Alongside them sit smaller structures called Ninots, which often depict satirical scenes (if you’re British, think Spitting Image).

Each is sponsored and built by a different casal faller, confusingly also often refered to as a Falla (similar to a community club). Each barrio (neighbourhood) can be home to tens of casal fallers who, throughout the year, pay membership fees, host parties and elect their Fallera Mayor (the closest equivalent example I can think of is the May Queen).

Depending on the members of the casal faller (whose donated money usually pays for the structure to be built), there will be different sizes and levels of complexity, but the vast majority will be at least 1.5x your height, with the highest-ever being 41 metres tall.

Over the five main days of fallas these monuments are exhibited, adored, given prizes and then, on the last night, they’re set on fire, ready to start again preparing for the next year’s fiesta. All against a backdrop of pageantry, explosives, and brass bands.

Why do Valencians celebrate Fallas?

There are many explanations as to why Fallas became such a huge tradition and point of celebration in the Valencian calendar. The one I’ve heard most often has been that it started when carpenters would clear out their old wood offcuts, burning them as Spring came, ready and renewed for the year ahead.

Over time, this morphed into a more ‘observed’ festival to coincide with St Joseph’s Day (the patron saint of carpenters). Having said that, though Fallas does have religious connections with the Ofrenda (flower offering) to the Virgin Mary on the 17-18th March, I understand that the festival traditionally is rooted more in the Pagan than the Catholic.

During the dictatorship, Fallas faced some restrictions as Franco clamped down on satirical commentary and criticism of the regime, as well as generally anything seen to be supporting regional languages and cultural practices. Despite these constraints, Franco himself seemed to enjoy Fallas, accepting the honour of ‘chief fallero, which was only officially rescinded in 2015.

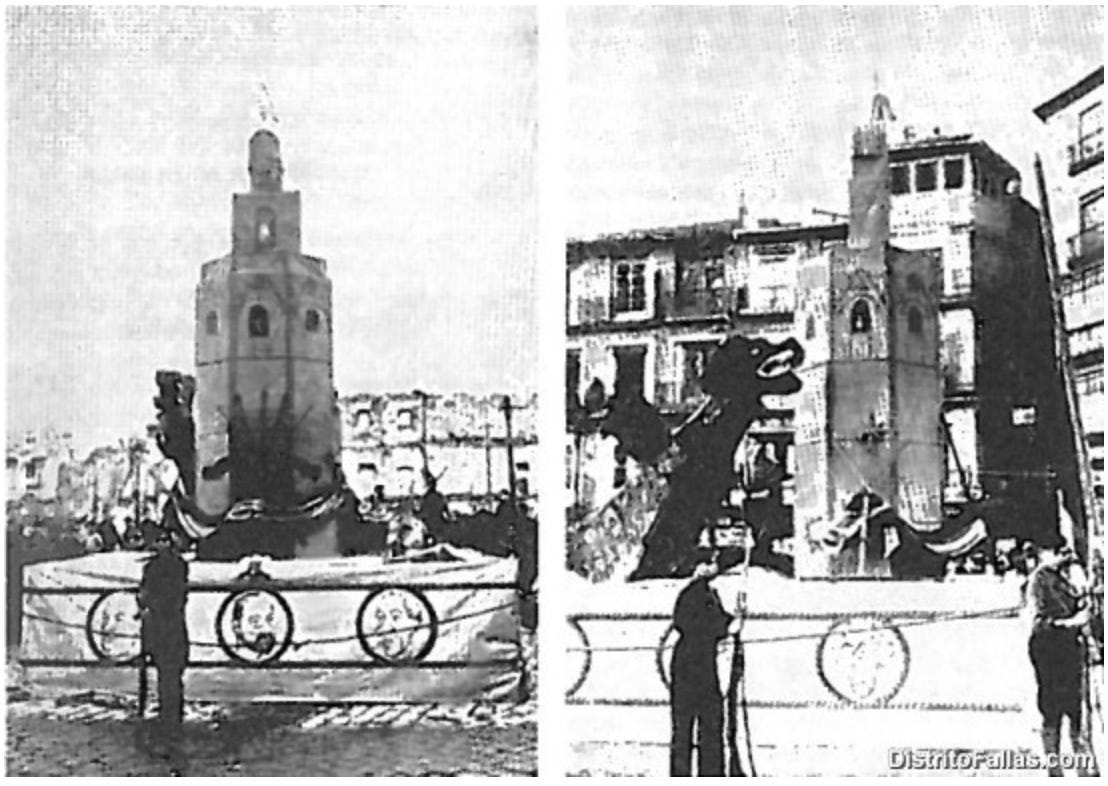

Maybe part of that was because Franco saw himself how Fallas was ripe for propaganda opportunities: this interesting article (in Spanish) on Fallas during the Civil War explains how Franco used a Falla himself in 1937 (albeit installed in Toledo) as a warning to Valencians to align with Franco’s cause. Similarly, the Valencians responded with four Fallas critical of Franco, though these were never built (only presented as drawings).

From 1975, with Spain transitioning to a democracy, the satirical nature of the Fallas and Ninots was back, along with full celebration of the festival again. Even just in the last few years I’ve seen anti-Franco monuments, ninots poking fun at the Spanish Royal Family, and others at the British. And last year, for the first main Fallas since the pandemic, there were a lot of Boris Johnson ninots. Sigh.

Another big reason that Fallas is still celebrated is the sheer amount of money that it generates for the local economy. Even though I still don’t feel like Fallas is super well known outside of Spain, it does attract a lot of Spanish tourists, and more-and-more overseas visitors. It’s estimated that three million visitors come to Valencia during this time. I always feel for the tourists who must book an airbnb wondering why it’s so expensive, then arrive here surrounded by drunk people and children wielding full-blown fireworks and consider ‘Valencia isn’t what I thought it would be’.

As well as the money that comes into Valencia for Fallas from outsiders, the ecosystem around the festival also moves money around the city. From the dressmakers and hairdressers for the falleros and falleras, florists for the ofrenda, artisans and carpenters for the 700 fallas constructed each year, the pirotécnicos who orchestrate the mascletás and fireworks displays, to electricity for the city lights, and the sheer amount of gunpowder bought. In 2008 it was estimated that Fallas boosted the Valencian economy to the tune of - and I can’t believe I’m writing this figure - 753,000,000 euros. Not bad for a street party, hey.

All that’s to emphasise that Fallas is a spectacle, but one that is rooted in every way in Valencia. It’s a great opportunity for many Valencians to express themselves, celebrate the seasons changing, and demonstrate the love they have for their way of life, all whilst having a very fun week off work.

Why do I love Fallas?

Honestly, I don’t always love Fallas. It’s loud, it’s noisy, it’s… a lot. Two nights ago, sick with this virus, I woke up to incessant explosions from 0130 until gone 2am. If you have pets, it’s horrendous for them - most of my friends with animals leave the city. The streets are packed and teenagers throw fireworks about with reckless abandon. I truly don’t say this in jest: if you have PTSD, you may want to skip this one.

But there’s no denying there is something special about it. It’s hard to put your finger on what that is, but it’s a feeling in the air. Excitement crackling along with the children’s shrieks and the gut instinct you end up with of ‘just knowing’ when a banger is about to go off. The Spring breeze rustling the Valencian flags draped along every street. The smell of gunpowder mixed with grease from the deep fat fryers on the churros stands. You’re alert to what could happen, and ready to be surprised on every corner, both at the same time. It’s something that whispers: winter is over… summer is coming. And then it shrieks loudly in your ear to labour the point.

I’ve picked a handful of Fallas components to give you a brief overview, this list is certainly not exhaustive!

Community: Fallas, falleros and falleras

Art: Fallas and ninots

Explosions: La despertà, la mascletà, firecrackers and fireworks

Flower offerings: La ofrenda

The city burns: La cremà

Community: Fallas, falleros and falleras

The beating heart of the Fallas festival is the neighbourhood falla, or casal faller. After all, if they didn’t exist then Fallas as we know it may cease to exist. Many were founded decades, if not centuries ago, and each is dedicated to honouring Fallas with their own band of falleros and falleras, and by constructing their own fallas and ninots to be burnt on the final night.

My understanding is that anyone can join a casal faller and become a fallero or fallera - you simply have to be willing to part with the necessary membership fees and donations. You also take part in the year’s calendar of social and fundraising events and vote for your Fallera Mayor (the young woman who will represent the Falla and have a shot at being voted the city’s Fallera Mayor for the following year).

Though some fallas gain sponsorship for their monuments, many are paid for by the members giving monthly donations or raising funds. At a beauty salon the other week, the lady serving me (a proud fallera), told me that sometimes, if the Fallera Mayor has a rich family, the father will pay for the monument that year as a dedication to his daughter (in a classic example of that other oft-celebrated festival: the swinging of dick competition).

As well as the money spent on fees and donations, it’s customary now for falleros and falleras to dress in the traditional silk dresses more akin to eighteenth-century Valencia, with intricate plaited hairstyles woven into gold adornments. I read that this move to traditional dress was only a relatively recent trend, but it has revived the silk trade and poured money into local dressmakers. The costumes can cost from 1,000 up to as much as 20,000 euros.

Being part of a casal faller is very important to those who enter into it. Often it’s something you will undertake your whole life, and perhaps continue on with your own family. It’s lovely to see that sense of community the activity brings. It’s completely normal to see paellas being cooked in the street outside casal fallers throughout the year, or women with their hair in intricate plaited buns even as they wear otherwise casual clothes.

Though God forbid you rent a place next to one. It’s up there with realising that the rubbish collection is outside your flat and you’ll be awoken thrice weekly at 2am by the sound of beeping trucks and breaking glass. You may need to invest in extra solid ear plugs or consider fleeing the city each March - just a warning!

Art: Fallas and ninots

This part of the festival is what I think really connects the festival with Fallas outsiders over the five core days of Fallas. Unless you are part of the casal fallers, after all, you are not privy to the rituals and work that goes on behind the scenes every other month of the year to make Fallas work. But for last five days celebrated, the streets fill with visitors along with Valencianos to marvel at the huge wooden and polystyrene sculptures and, in many cases, try and tick off as many as possible.

These monuments are a cottage industry in themselves and there are whole industrial units dedicated to artistas falleros, who spend months building these enormous and intricate statues. All Fallas must be up by the 16 March and the night of the 15 - 16th is called La Planta, where the artesans work through the night to erect them and put on the finishing touches; a bit like Bake Off, when it’s done, it’s done - no final touches!

It’s fun walking home through the streets during the days before La Planta - the Fallas are beginning to take shape, often the core elements are there. Sometimes you think they’ve already finished it, and when you go back on the 16th you’re amazed to see it was nowhere near done.

Because the Fallas are built from donations, you tend to find that the richer neighbourhoods have bigger Fallas. The costliest Falla was a cool 900,000 euros. And yes, it still got burnt like all the others.

Bigger doesn’t always mean better, though, and more recently concerns about the environment and cost-of-living crisis have led to ‘fallas alternativas’ (alternative, experimental fallas), where casal fallers have chosen to spend less money and use more sustainable resources for building their Fallas. These can often be the most thoughtful and interesting ones. Personally I find that all the Fallas that follow the same cartoonish style can become a little boring after a while, even whilst I respect the craftmanship and time that has gone into them.

Once they’re up, one of my favourite things to do during Fallas is to finish work, meet friends and pick a neighbourhood or two. We buy a beer from the street vendors and head from intersection to intersection, taking photos and making sense of each of the satirical ninots, many of which are about regional politics so go right over our heads. There are usually Fallas we find a bit naff, or outdated (there are a lot of rather suspect depictions of other cultures, and some barely clothed, big-breasted women), but there are always a few that completely blow you away. And those are usually the ones you want to come back and watch burn, interestingly.

Explosions: La despertà, la mascletà, fireworks and firecrackers

If the Fallas monuments are a big part of the sights of Fallas, well this next section is all about the other sense stimulated: sound.

Fallas must be the noisiest, loudest, fieriest festival in Spain, if not the world. The sheer number of bangs you hear on a daily basis are enough to make you question why you moved to this city.

Every day from the last Sunday of February you’ll notice it, the cracks and booms ratcheting up to a full-on crescendo for the last five days, following the natural rhythm of the mascletà. I have more than once been left with muffled hearing and ringing ears from a normal day out during Fallas.

As a relative outsider, you’re always able to tell that Fallas is coming because suddenly small children become a terrorist threat, stumbling through the streets as young as eighteen months carrying a little box around their neck. Inside are tiny petardos, or firecrackers, which they gleefully throw on the street. By ages 6+ they’ve progressed to heftier firecrackers, and at 12+ they’re setting off full-blown rockets.

This video below, though not of kids, shows men holding fireworks the way we in the UK were told to use sparklers. Let’s just say, Valencians would be open-mouthed learning our firework safety: the sheer idea of anyone using gloves and sticking your used firework in a bucket… We would be laughed out of the room.

This period is the only time that fireworks are allowed to be sold and used in Valencia (hence why everyone’s making the most of it), and suddenly petardo shops that you’d never noticed before fling open their doors to satisfy the pyromaniac desires of Valencianos. It’s a curiosity to me that these shops are not used for anything else the other eleven months of the year, and must give an idea as to how much money they make in that one month.

Now, most cultures love fireworks, or at least have them tied to key celebrations during the year, New Year’s Eve being one of them. But Valencians love them *so much* that they set them off during the day as well. In fact, the despertà and the mascletà, two central elements of Fallas, are less about the colours and pretty formations on display, and more focused on the bone-shaking energy of the explosion.

First: la despertà. Picture the scene. You decided to have a long weekend in Valencia at the end of February. Maybe you stayed out late on the Saturday night, in the Spanish style. No problem: the only thing you have planned Sunday is a lazy paella by the beach after a long lie-in. Until, suddenly, you’re awoken at 7:30am by the sound of explosions. You can’t mistake it for a car backfiring because it’s already happened again, and then again and again. The glass in the windows are shaking from the earth-shuddering bangs, and you can barely hear yourself think for the sinister whistling that comes before the bang. You look out the window. No one seems to be panicking. Are we under attack? Is this a normal Sunday in Valencia?

No, it’s not, but it is a normal last-Sunday-in-February morning, which is when Fallas season officially kicks off. This is the despertà, and if you don’t know what it is then, somewhat like the mascletà, it’s initially borderline terrifying. The story above did happen to me, the first time I experienced Fallas in 2018 and, though my gut told me nothing was really wrong, I have to admit that I was half-thinking ‘should I be worried about this?’ - a bit like when the fire alarm goes off at work.

La despertà essentially means ‘the wake up’ and yes, you certainly do, when falleros, falleras and other pyromaniacs are stalking the streets of the neighbourhood towards the ayuntamiento (where I was staying next to, that time), throwing firecrackers. A bit like this video shows (courtesy of distritofallas.com).

Once they reach the Ayuntamiento (town hall) there is a terremoto display (earthquake-like pyrotechnics, a bit like the sound of the mascletàs), which uses the very heavy-duty explosives and was what woke me up that morning years ago. The early-risers are then rewarded for their hard work waking up the neighbourhood with a cup of hot chocolate, which really should also be offered to all residents within a mile radius of the town hall.

The despertà then happens again every morning at 0800 during the core 5 days of Fallas. Often the fireworks are accompanied by brass bands accompanying the falleros. It’s fun the first day or two, after day three you’re hoping they switch up the repertoire.

Now, onto the mascletà, probably my favourite bonkers thing about Fallas after la cremà. Many people hate the mascletà with a passion, others love it so much that I have seen middle-aged men cry and embrace one another after watching a particularly good one.

From 1 March to 19 March, every day at 14:00 in the town hall square of Valencia, a truckload of explosives are ignited as crowds watch from just metres away. It usually lasts between five to ten minutes, in which time the square fills with so much smoke that you can’t see the elegant buildings in the square, let alone any sense of what we’d call ‘fireworks’.

That’s also because the mascletà is not really about colour or light, it’s about energy, rhythm and motion, moving through your body, dialling up slowly and then suddenly rising to the stirring, deafening crescendo.

I’ve seen maybe five or six mascletàs, and noticed that each tends to include the following:

Every mascletà is preceded by a ‘warning shot’, or rather bang, at 13:50 and 13:55. It always reminds me of the ‘Posts Everyone!’ scenes in Mary Poppins where the Banks family have to get ready to hold everything for when the old Captain lights the cannon. A mascletà is not dissimilar to that 8’o’clock bang, it just lasts longer.

All are ignited by the Fallera Mayor, who stands on the balcony with her entourage. She lights the trail leading to the mascletà and begins the ceremony, at 14:00 sharp.

The mascletà begins with a few, distinct explosives that most resemble what others see as fireworks, with plumes of colours rising up in the air to signify the madness has begun. Common colours are those of the Valencian flag: yellow/orange, blue and red. Since the war started there have also been nods to the Ukrainian flag colours too.

It continues with a ranging number and rhythm of bangs, a mix of explosive booms and the whooshes of fireworks.

As the mascletà nears its climax it hits the terremoto, or earthquake, stage. The bangs get closer together, louder, and more frenetic, you can’t really hear the whooshes anymore. It’s a little like when you clap your hands slowly in a theatre, then get quicker and quicker and louder and louder until the energy and rhythm has accelerated. The bass takes over!

The finish is signified by a handful of close, sharp bangs after a lull in proceedings.

And finally, the pyrotechnic operator responsible is often lauded - they’re sort of like local celebrities.

It’s hard to explain what a mascletà feels like, because it’s so singular. But I can see why people cry. A mascletà can start off anti-climatically, with the odd bangs punctuating the blue sky in a disjointed way. You think, hmm this isn’t going to be one of the best I’ve seen. And yet, once it hits its stride, you feel your body moving along. Your ears are ringing, you’ve opened your mouth slightly as all the abuelos advise, to save your eardrums bursting, but you still feel a pull forward regardless of the fact you can’t go further than the person ahead of you. It’s like the rhythm is pulsing up through you, from your feet and up into your whole body, to the point that I often feel my chest and neck begin to push upwards and out.

The odd fireworks whoosh up, cutting through the bass of the explosives booming against the stone and tarmac. As it nears the climax, the beats get faster, closer together, the whole crowd starts to move like you do, people bounce on their feet or raise their hands. Some start screaming or shouting, they start punching the air. The final three or four or seven bangs (I’m never sure by this point, lost in the finale) are like morse code, signalling the whole drama is coming to an end. And when it does with that last crackle, the whole crowd erupts. People hug and laugh and cry, then hurry off for lunch, full of commentary on just how good that one was compared to yesterday’s.

Here’s a video of a full mascletà to get the full idea (video not by me).

Flower offerings: La ofrenda

The ofrenda is the part of Fallas that feels comparably restrained to the rest of festivities. It’s also the element that appears more religious, as it marks the procession of the falleros and falleras to the Plaza de la Virgen where they offer flowers to an icon of the Virgin Mary.

The procession happens over two days, on the 17 and 18 March throughout the city centre of Valencia. It’s quite something to see the hordes of exquisitely dressed falleras solemnly proceed towards the centre of town, of all ages, and dressed in all colours, all with their bouquets.

Once you’re in the square, the smell of the flowers first hits you, and then the scale of the spectacle. The falleras stop and bow their heads at the base of the Virgin Mary, who starts off as an empty wooden structure. They pass their flowers to attendants at the bottom who throw the flowers up to others who add them to the frame. The flowers eventually become Mary’s dress. If you look at the photo below, you can see the attendants at the base of the statue, with some gaps where there are no flowers yet. Also on the left hand is another frame which will be another piece of art made up from the remaining flowers.

The procession is deeply moving to watch, as well as for those taking part. It’s completely normal to see falleras moved to tears as they complete this annual ritual, and more so in the first Fallas after Covid in 2021 (which for the first time were held in September owing to the early 2021 lockdowns).

The final flower offerings are left in the square for days after before being removed.

The city burns: La cremà

We all know the best is saved until last and that includes my favourite part of Fallas, La Cremà.

(OK, actually the cremà has to be last anyway because that’s the moment that all the Fallas across the city are set on fire).

Starting from 22:00 on the night of the 19th March (though, realistically, it’s usually no earlier than midnight) the first Fallas are set alight, beginning with the smaller, children’s sculptures before taking a light to the giants. The fallas burn quickly and usually without any issue, being designed to light easily and structured so they fall in the safest manner.

First each Falla is packed with fireworks. Then the whole casal faller of falleros and falleras gathers around the monument, ready to set the first firework alight, which will take the whole falla up with it, they go a bit like dominoes. You can see the moment on this video below. For the bigger Fallas, you need to wait for the bomberos, or firefighters, until you can go ahead.

When I first experienced Fallas, having seen the size of the parties every night, I assumed that the last night would be another huge party with all the falleros wanting to go out quite literally with a bang. But in reality the night of La Cremà is very emotional and solemn, and you can feel that subdued energy across the whole of the city - like Sunday blues, on a bigger scale.

It’s also normal to see the Fallera Mayor for each falla crying as their Falla monument burns. Not only is it the end of another year’s celebrations, but it’s also the end of their reign.

The burning of the Fallas is often the part that most outsiders can’t get their heads around. I also find it hard sometimes. First off, you have the noxious plumes of smoke released by setting fire to such quantities of painted polystyrene. If the thick black clouds heading your way don’t worry you, just take a look at the air quality levels in Valencia the day after Fallas.

Second of all, it’s hard not to think of the sheer amount of money spent on these statues and marvel at the obscenity of it all, especially in times of hardship. Across the board, hundreds of thousands if not millions of euros are spent on creating these artistic objects, only for them to turn into dust. I thought I was bad buying scented candles. And even madder, the very next day they begin to plan the next year’s sculptures. It’s like painting the Golden Gate bridge.

Yet despite all this I still find myself drawn back to watch the city burn (I’m gutted to be missing it tonight thanks to sickness). Who could resist the bewitching allure of the Cremà, an especially potent symbol of renewal, rejuvenation and, in some ways, redemption.

I was reflecting on this symbol looking at Fallas today, when I finally felt well enough to leave the house for a couple of hours to see some of 2023’s selection. An incredible cat Fallas (by escif again) was accompanied by this charming little ninot of a ‘maneki-neko’ chinese cat figure.

The inscription suggests that you take an offering and ask the cat a question, before pulling its hand for an answer. I was struck by the number of people who were leaving messages, some you could read.

One man neared the statue, put his piece of paper down, bowed his head and audibly mumbled some small hope or prayer before pulling the cat’s paw. He then stood back and reflected, before re-joining his group, knowing that his wish, his promise, his burden (for who knows) will go up in the flames tonight. The slate clean, ready to begin again tomorrow.

That to me, epitomises Fallas. Celebrating the rhythm of life, the steady passing of the seasons, each with their own particular smells, sights and melodies. A reminder to open your eyes in the here and now, savour the present, and don’t become too attached to the material - they’ll only slip away one day anyway.

I hope you enjoyed this tour of Valencia’s most famous festival. It’s really nothing until you experience it yourself. Just remember to book in advance, bring ear plugs if you want to get any sleep, and open your mouth when the mascletá starts.

FANTASTIC read. You put me there with your writing and I thank you. I could've made a terrible mistake. Now I know I will NEVER under any circumstances visit Valencia during Fallas. When I read the title before the essay, "Fallas" brought Manuel de Falla to mind because I love "Nights in the Garden of Spain." Anyway, it's terrific. I hope you're on the mend.

you live in Valencia! been dreaming about moving there for a while, this is a great read x